Patrick’s Pet Care Brightens Brookland

By investing in local artists, small businesses can fuel D.C.’s creative communities.

This article was sponsored by Patrick's Pet Care

If you think cafés, restaurants and offices are the only businesses that partner with local artists, think again.

You might not expect Patrick’s Pet Care — a D.C.-based full-service pet care firm — to partner with local artists. But when you step inside the Brookland headquarters or join the more than 30,000 people who watch the doggy daycare livestream annually, you’ll spy original artwork in a range of media.

Local businesses can strengthen D.C.’s arts scene and create opportunities for artists by making intentional choices about what hangs on their walls—and get something beautiful in exchange.

Read on to learn how three collaborations with local artists have brightened up Patrick’s Pet Care.

Art Enables Connects Galleries, Collectors and Clients With Artists With Disabilities

As clients wait for a Patrick’s Pet Care team member to fetch their pet from the doggy daycare playroom, they might spy a series of colorful paintings hanging on the wall. In one, a mustachioed Flynn high fives a German shepherd; in another, the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception is bathed in sunshine while Flynn walks a dog nearby.

Both paintings are the result of a commission from Art Enables, a nonprofit gallery and studio space perched on the southern edge of Brookland.

Being a working artist is difficult for anyone, but artists with disabilities face additional challenges breaking into the art scene and finding financial stability. Art Enables’ small staff supports artists with disabilities, connecting them with resources that make art a viable career path.

Unlike art therapy programs, which can aid motor skills or provide emotional release, Art Enables is focused on professional development. “We try to ensure that our artists have the opportunity to not only make their work in the studio but also sell their work here,” says Courtney Smith, Art Enables’ development and communications manager.

Staff members provide support, from navigating commissions to arranging shows in galleries across the District and around the world. For many of Art Enables’ more than two dozen artists, the income they earn from selling artwork translates to important financial freedom.

In addition to gallery sales, Art Enables staff members help artists secure commissions. When Patrick Flynn, founder of Patrick’s Pet Care, requested an artist who specialized in animals, Frazier immediately knew who to suggest. “That's Jackie's MO to a tee,” she said.

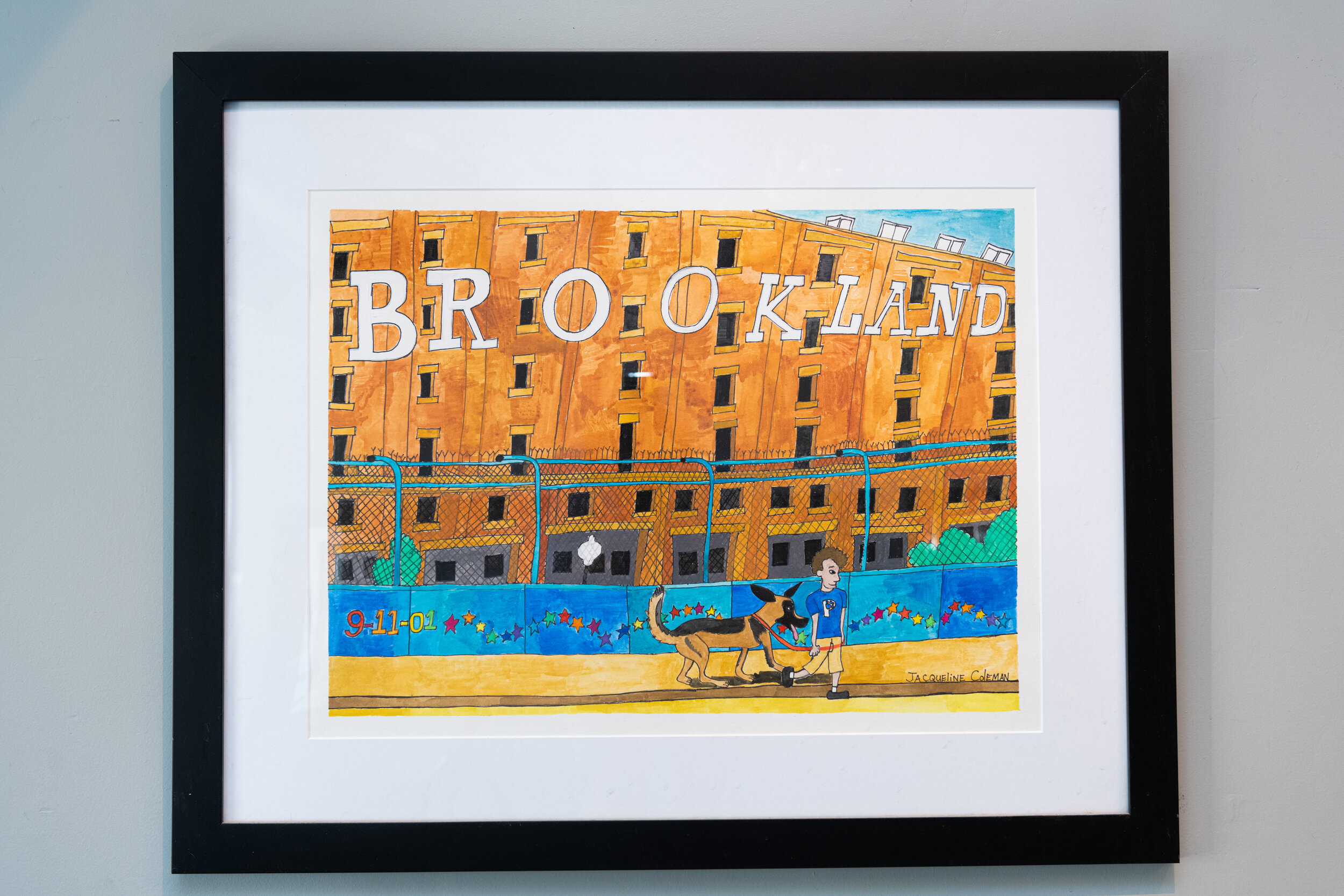

Jacqueline Coleman, a soft-spoken artist who works in vibrant colors, is known for her paintings of animals. She loves “anything cute,” channeling her sense of fun into her artwork. She recently created a series of four paintings for Patrick’s Pet Care.

As a self-taught artist, Coleman’s watercolor technique is experimental. While most watercolor artists use layered washes of color, Coleman pushes the form by opting for a minimal amount of water. As a result, her paintings are highly pigmented with a flat, graphic style.

Like Coleman, many artists with disabilities are self-taught and develop techniques that defy the art school-mandated status quo. Art fairs such as the Outsider Art Fairs in Paris and New York and museums such as the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore celebrate works by self-taught artists who introduce new ideas into the art world.

Frazier says this is an important part of Art Enables’ mission, too. “The art world would miss out if we weren't promoting and getting their work out there because it is so different than contemporary art and what's shown in a lot of galleries right now.”

Organizations such as Art Enables exist across the country, from Austin to Chicago, Portland to Kansas City. Together, they form a network that promotes artists with disabilities and ensures that their work is seen. “We believe that our artists should have an opportunity to be able to have their dream job,” Smith says.

Creating Sculpture at a Dog’s Eye Level

Pet owners are greeted by a large wooden sculpture when they walk into Patrick’s Pet Care’s Brookland location. The artwork, created by local sculptor Charles Bergen, hangs on the front desk at dog’s eye view.

The piece commemorates the haunting story of Momma, a local pitbull who inspired a major reform in animal abuse laws — then disappeared before community members learned of her fate. The sculpture, and Patrick’s Pet Care’s entire Brookland location, are dedicated to Momma in order to raise awareness of D.C.’s Standard of Care for Animals Amendment Act.

In January 2017, as an icy cold front plunged D.C. below freezing, Ward 4 Council Member Brandon Todd received a flood of emails. Community members were distraught over the plight of a pitbull with gentle eyes and visible ribs. The dog, Momma, had been left outside for days, with only a thin wooden structure for protection against the bitter cold.

The situation presented a moral dilemma while exposing gaps in D.C.’s laws. Distressed neighbors considered trespassing to rescue the shivering dog, while Human Rescue Alliance officials explained that the owner was not technically violating the law. Officials were careful not to overstep their jurisdiction because removing Momma could imperil their ability to rescue neglected pets in the future.

The Council unanimously passed an emergency measure that could protect other pets from Momma’s situation. Although neighbors stopped seeing Momma, the law has provided greater protection for pets exposed to extreme weather. A small plaque explaining the story hangs next to the sculpture, and Patrick’s Pet Care distributed replicas of it to the local lawmakers who enacted the new legislation.

Momma’s story moved animal lovers across D.C., including Bergen, a sculptor known for creating interactive installations that often depict animals. A native Washingtonian, Bergen’s love of animals blossomed during his childhood in leafy Cleveland Park. Through his interactive, approachable installations, Bergen aims to create sculptures that replicate animals’ ability to command space.

Bergen agreed to Flynn’s proposed commission, which would pair the sculpture with plaques he planned to distribute to the local legislators. Bergen was working with an assistant, BreA James, who created the initial drawing of Momma. From there, Bergen selected a combination of southern yellow pine and American walnut, which he carefully layered, glued and shaped. The finished work commemorated a rare example of expedient collaboration between community members and legislators.

Creating the sculpture of Momma reminded Bergen of his own Rottweiler’s tender fragility. “You know, the same sort of big, friendly, bulky dog,” he says. “People think they're great, big, indestructible beasts, but they're not.”

Painting New Murals While Paying Homage to Graffiti

As Patrick’s Pet Care expands to occupy a neighboring property, Flynn has searched for ways to beautify the spaces where clients’ dogs will spend most of their time. To this end, he recently commissioned a series of murals from Nessar Jahanbin, an artist whose work can be seen on buildings through D.C.

When Jahanbin moves through D.C., he notices walls: Half-built walls in the process of becoming condos; businesses’ walls neighbored by litter and leaves; big, blank walls that stretch out like empty canvasses alongside highways and railroad tracks. Jahanbin began painting murals in 2011 or 2012 while still working as a clerk at a law firm. He was drawn to the community created around practice walls, where aspiring graffiti artists could legally experiment with spray paint and refine their techniques, learning from more experienced artists along the way.

Since then, developers have increasingly carved up D.C., and practice walls are disappearing. Today, Jahanbin says there’s only one left. Without them, there are fewer ways for graffiti artists to legally hone their craft and less opportunity for informal communities to gather.

Despite these changes, one thing remains the same: Murals can be magical. Neighbors and passersby sometimes change their daily routines so they can walk by, watching an image develop over a series of days.

Jahanbin also enjoys watching neighborhoods undergo subtle transformations. When a new mural appears, litter tends to be cleaned up more promptly. Sidewalks are swept, porches are straightened. People want their neighborhood to be a worthy frame for the fresh artwork.

Painting on the street also allows the world into the artistic process. Jahanbin is regularly interrupted by curious passersby — some who offer frank feedback.

“It makes you question yourself a lot,” he says. Passersby have the opportunity to comment on unfinished art or challenge it by asking questions. Sometimes, people ask why he’s painting a historical figure, then tell him stories about little-known but influential individuals. “Then you start thinking, ‘Wow, I didn't look at it like that. Now, I'm reevaluating what I'm doing.’”

Jahanbin says this feedback is invaluable. “If you're in your studio painting something, you can be like, ‘Hey, this portrait I did of this famous person in watercolor, it’s beautiful, I love it.’ You can sit back, admiring it,” he says. “You don't have the opportunity for someone to walk by and say, ‘Hey, his lip looks kinda funny.’”

At Patrick’s Pet Care, Jahanbin plans to create an optical illusion for pet owners who check in on their furry friends via webcam. He’s planning to paint a field that will make the walls melt away, using tricks of perspective to create a seemingly endless dog park that will cover the plain walls. It’s the first of several possible murals, including one featuring presidential pets.

There will always be people who view graffiti as vandalism, a problem that may grow worse as D.C.’s practice walls shrink more and more. But it’s undeniable that art can shape a city, commanding attention and replacing emptiness with vibrancy.

Small businesses can play their part by commissioning murals, paintings and sculptures. When businesses invest in original artwork produced in their communities, they can provide more beautiful spaces for clients and employees — and ensure that artists can stay in business themselves.