Q+A: The Making of Knox Roxs

Jennifer White-Johnson creates Multimedia Artwork that celebrates the autistic community.

Questions by Michelle Delgado Answers and Artwork by Jennifer White-Johnson

For one Saturday last summer, artists and zine-makers took over the National Museum of Women in the Arts for D.C.’s annual Art Book Fair. Among them was Jennifer White-Johnson, whose warm smile and colorful table drew in passersby.

White-Johnson is an assistant professor of visual communications and digital media arts at Bowie State University, an HBCU just north of D.C. She’s also a multidisciplinary artist and an activist who is passionate about advocating for inclusion and equity, particularly for people of color and neurodiverse people.

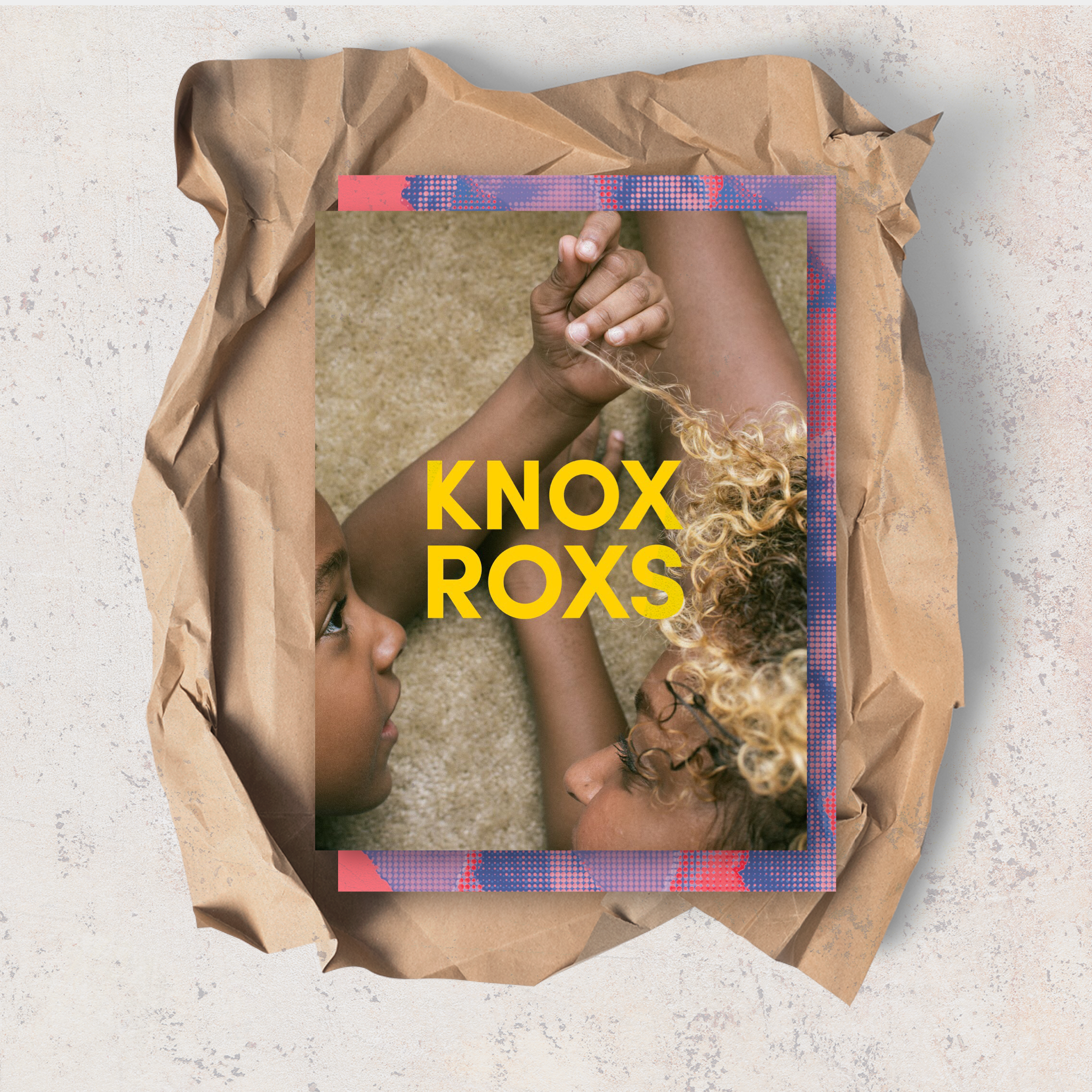

For White-Johnson, art and identity are closely tied. At the Art Book Fair and around the world, her zines, posters, stickers and buttons represent an important collaboration with her Autistic son, Knox, and the larger Autistic community. In late summer 2019, we connected with her by phone to talk about it all.

This conversation has been lightly edited and condensed.

—

SUMMERHOUSE

Your work spans multiple disciplines. How do you sum up your work these days?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

I'm a mom and an educator and an advocate. When I finished my graduate studies at Maryland Institute College of Art (MICA), I was always running into former professors. They're like, “Oh, you, you just graduated, you should come back and teach.” I was always open to those opportunities. Teaching is definitely the full-time experience where I'm really immersed in academia, community learning, and making immersive experiences for students. I'm also an advocate — I believe that art can completely empower and transform.

When I became a mom, the direction of my work shifted into something extremely powerful that I never even saw coming. I’ve always been an advocate for kids, especially kids of color and kids who are marginalized or disenfranchised. They’re not always given opportunities to make art. When I became a mom, I was able to infuse all that fun stuff into my art-making experiences with my son.

With him being on the autism spectrum, that allows for me to just have more fun. This is my life, so I get a chance to frame the whole experience the way that I want. And plus, he's my kid! I have him all the time, so I'm able to really cater and adapt the experiences so that they work for him and for us as a family.

SUMMERHOUSE

What is it like to make art with your child? How does that impact your relationship?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

I’m a first-time mom. I was 31, 32, so I was still experiencing womanhood and navigating that whole chapter of my life. I was still trying to discover myself.

[My approach] came from me observing other artists [who are] moms and really enjoying how they felt comfortable incorporating their kids. There are a few collectives in Baltimore that are artist-mother collectives, where the space is very inclusive to bringing your kids so they can be a part of your art-making.

I knew that I could be super, super busy and never see my kid and complain about it. I could be exhausted and tired, and then our relationship would reflect that. Or I could make sure that any side projects I involved myself with would [center around motherhood and family]. Once I decided to just do that, I felt so much more balanced.

SUMMERHOUSE

How does the Autistic community factor into your work?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

As an artist, it's very easy to work by yourself, articulating your particular vision. But when it was time to start diving into autism and Autistic lives, I knew that I had to be able to include Autistic voices, especially [Knox]. It was really important for other people to see, “Oh, so this is how his mind works, and this is how he's expressing it,” to help to break the stigma.

There are a lot of Autistic artists and communities and collectives. It’s great, but they have to work really hard to get visibility. I'm not Autistic, so I need to make sure that my work isn't about just about Autistic folks. It’s like, this is me as a mom, and this is how I want to be able to advocate and respect and listen to them. This is how the work is informing my outlook on life, on autism and in general.

In addition to the artwork that Knox and I make together, I spend a lot of time sharing it with other Autistic folks because I want to get [their feedback]. Like, “We get this, this is amazing and this represents us!” I also want to be able to know, like, is it cool? Do you like it? Is it a really cool reflection of how you want to be depicted?

SUMMERHOUSE

When it comes to depicting autism, how does your work address hierarchies and gaps in representation?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

[With autism,] the hierarchy is, “I'm the clinician, and I gave you the official diagnosis, so I'm going to tell you how to live your life.” There's no talk about how we are going to live our everyday lives as people, and what are some of the fun things that we're going to do together as a family to accept everyone's differences — and everyone’s identities, period.

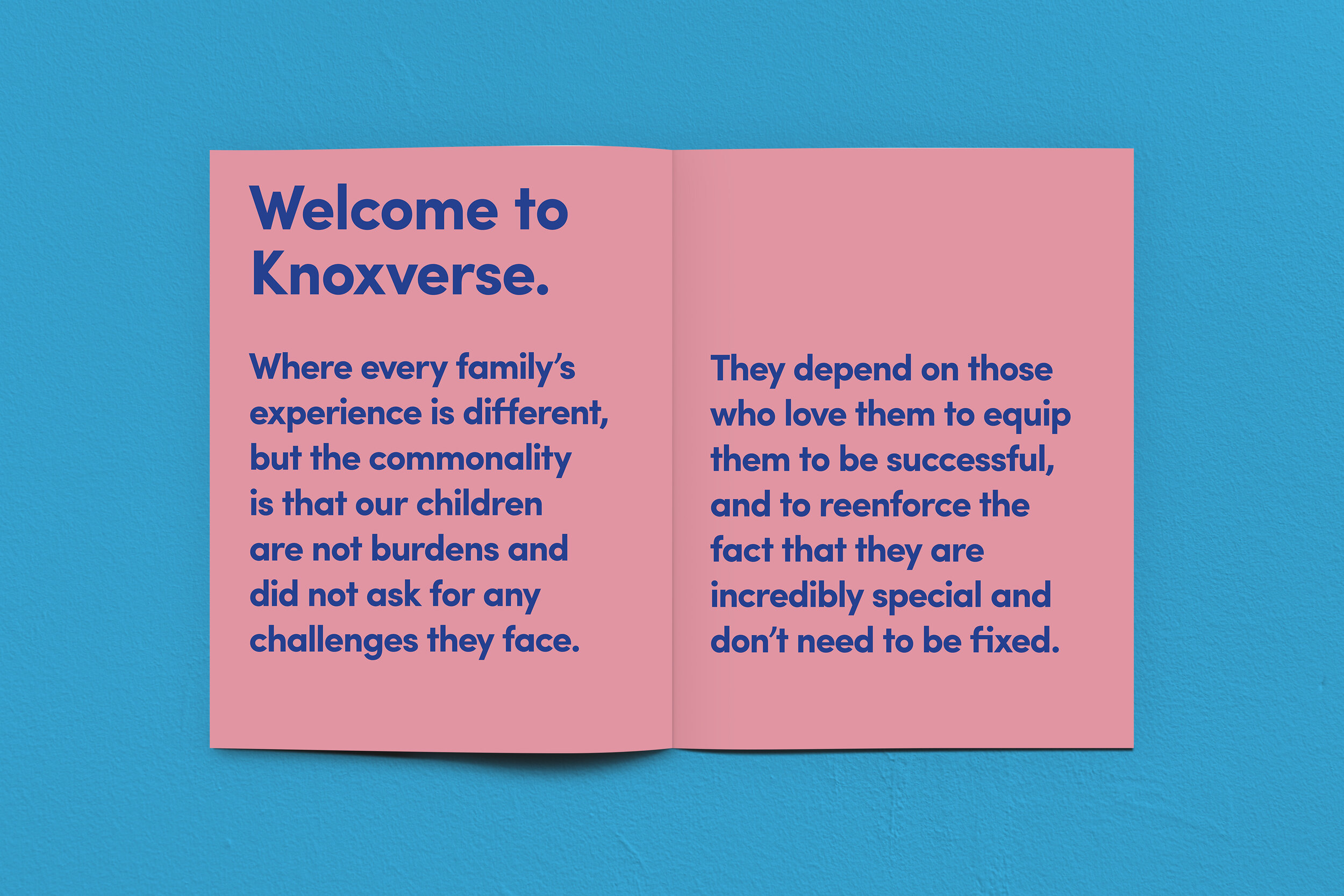

The zine was never meant to be this [diagnosis] of, “Oh, so your child is Autistic? These are the next steps.” It was intended to [say], “Our son is Autistic, and this is how we celebrate him.” We want for him to grow up in a world where he sees himself depicted in a really beautiful, positive way.

“Homie House Press called and said, Hey, the Met has purchased many of the books in our cannon, and guess which one that they want? Knox Roxs.”

SUMMERHOUSE

Can you tell us more about what it was like to launch Knox Roxs through Homie House Press?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

Homie House Press is co-run by two amazing femmes [Adriana Yvette Monsalve and Caterina Ragg]. They're my heart, I love them so much. They tell stories about all different types of identities — queer folk, trans folks, border stories and stories that bring to light folks who just deal with identity. Basically, the beauty of just exploring your whole life, your whole self, your whole identity. The launch went well because I was very thoughtful about who I wanted to be my editors and who was going to be a part getting the narrative out there.

It was amazing. Adriana is here in the U.S., and Caterina is in Milan, Italy. And so, the launch was massive — it was distributed to every book fair in the United States and all over the world. Literally, the book was published in October, and in November, Homie House Press called and said, “Hey, the Met has purchased many of the books in our cannon, and guess which one that they want? ‘Knox Roxs.’” [The zine is now] part of [the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s] research center, the actual library where educators and students can come and have an intimate moment with this book.

By December, [the zine] was already in London, [where] it was part of a pop-up exhibition at the Hart Club, which is a gallery space and a store that champions neurodiverse artists.

Because of the time difference, I was like, “Look, I obviously can't be in London for this opening. But can you guys send me footage so that I could share it?” They were on London time sending me images at 6:00 a.m. my time, and God knows, it’s 10:00 p.m. my time, but we'd be going back and forth and sharing images.

And then, [more opportunities kept coming]. It was like, “Hey, we're having another exhibition. Are you interested in submitting work?” “Hey, we're having another show, would you be interested in sending us some images, and we'll print them?” It's this beautiful opportunity, these long-lasting partnerships and relationships with people who see you and people who respect and get you.

In February of 2019, my husband and I went up to the [Metropolitan Museum of Art’s] library. It was so important to me to be able to [see it] in the flesh. Because, again, [it shows the importance of] being very mindful of what you put out there, what you publish, because it could make waves. You don't know whose hands that book can be in.

Since the launch, it's been in the right places. The right folks have been asking to understand the backstory. Educators, especially — those are some of my favorite folks. They're there with the students every day. They have the academic knowledge of how they should be working with these kids. But let's talk about their souls, let's talk about their identities and how those narratives should be celebrated. We often don't get a chance to see those narratives celebrated, or they're just depicted in a very stigmatizing way.

SUMMERHOUSE

As an advocate, what are some of the ways you encourage people to include Autistic folks in their lives and creative work?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

I'm always very careful about the language that I use and about how I depict Knox. Listening is a huge part, because [Autistic people] just want to be heard. Everyone wants to be heard, listened to and respected.

That's why it was important that [I wasn’t saying,] “Oh, here's my kid, and he's such an inspiration. And these are all the ways that we have such a hard time.” It's about praising all his fun quirks.

The more I shared [my zine, Knox Roxs], the more it became this really cool conversation. It helped me create an exchange between other Autistic people or even other Autistic parents, young and old.

SUMMERHOUSE

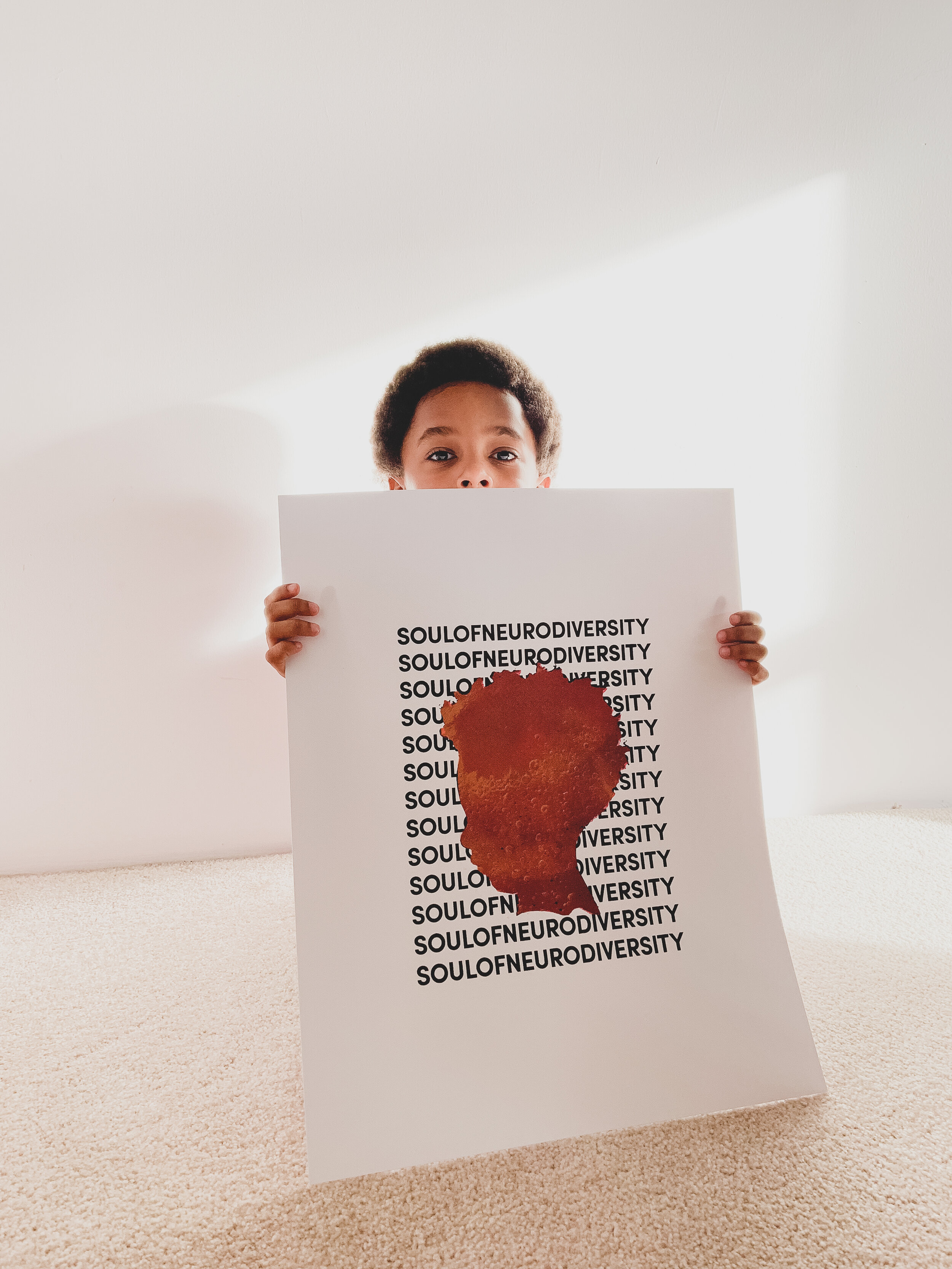

We've talked about soul and soulfulness — those are words that keep coming up. At the Art Book Fair, you sold posters that had the phrase “Soul of Neurodiversity.” What does that phrase mean to you and your family?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

[It’s about] highlighting neurodiversity and celebrating how the brain itself can be this magical place, this diverse place where you can just think and feel the way you want to as an individual. The soul is basically depicting those narratives we don't regularly see or [rejecting] these very stale narratives that are showing us a very small piece of the picture.

The apparel and products that I see are often designed with messages like, “I have autism, but autism doesn’t have me,” or “I’m not my autism.” They're trying to combat autism as this illness — like it’s this hunker-down illness that's going to kill you.

There are different aspects that a lot of Autistic people are living with, whether it's anxiety [or other accompanying conditions]. Those are things that [Autistic people] work with every day, that they navigating life with. It’s really just about being told that it's okay to have anxiety, that it's okay to not be okay today. I think it's important for them to be able to vocalize that and feel comfortable saying, “Hey, I need help.” Asking for help is one of the biggest forms of advocacy they can do.

It’s also about language that sounds poetic and beautiful. That's different from the language that Autistic people normally see associated with them, [language] that they may not have even sanctioned or approved. Their voices, their experiences, their opinions, their lives — those are the main things that they feel are being misinterpreted or abused.

SUMMERHOUSE

How does DIY factor into your work?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

It's so important. DIY culture means that you have more authority over how you create the work and how you articulate your own experience. It's a form of reclaiming the narrative.

[As] an artist, I see disability as this amazing chance [to say], “Hey, I'm going to take myself, this beautiful identity that I have, and I'm going to be able to just create artwork, period. Because it's just me exploring whatever I want to express at the moment.”

Btrcp was another Autistic artist at the D.C. Art Book Fair. They approached me a week or so before the Art Book Fair, and we had this really great exchange. I was telling my husband, “Yeah, this is why we do this” — to make these connections with other neurodivergent folks. They need to be able to see people that look like them so that they can continue to feel safe and accepted and supported.

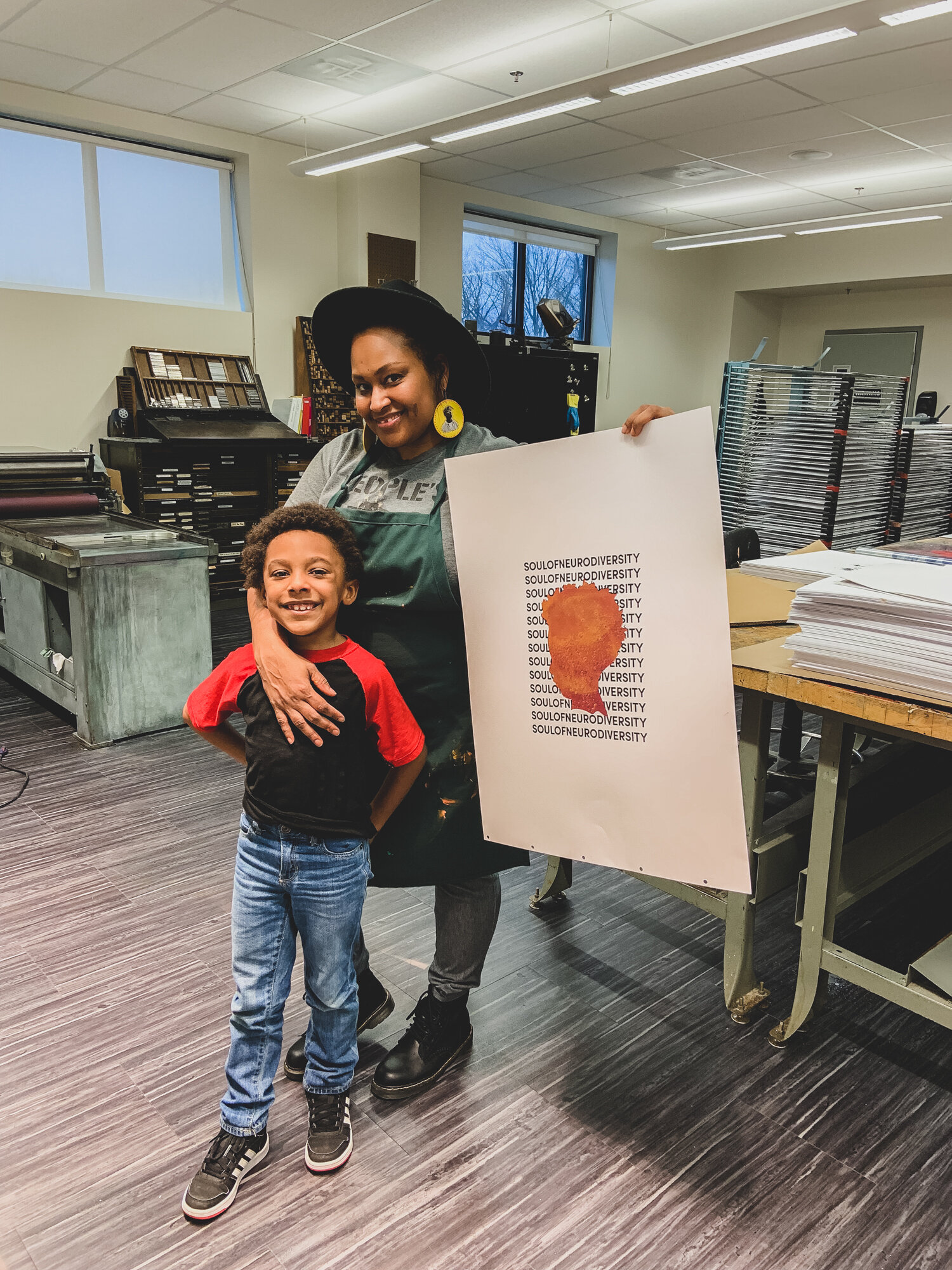

Community also means I have authority. I have more say about how I publish, how it looks, what gets done, what goes in and what doesn't go in. I get a chance to mix and dabble in a lot of different mediums. Since the zine release, I knew I wanted to continue telling stories about immersive art-making experiences with Knox — screen printing, digital artwork, playing with animated GIFs, playing with music and movement. He has so much that's inside of him already, music and rhythm and laughter and so much joy.

Now, it's just continuing to find ways that you can continue to express that and feel that he doesn't have to be ashamed when he wants to be really loud or when he wants to dance a certain way. Because again, [Autistic people are] often stigmatized. It’s like, “Oh, they're acting out.” Or, “Why are they so loud?” Or, “Why don't they shut up?” It's like, are you even listening? Or are you just judging?

“The brain itself can be this magical place, this diverse place where you can think and feel the way you want to as an individual.”

SUMMERHOUSE

In addition to having an important message, Knox Roxs is also beautiful to look at. Can you share more about your goals for the zine’s design?

JENNIFER WHITE-JOHNSON

Design, whether it's aesthetic or the designing of space or experiences, helps to foster community. It helps to encourage that reclamation of space. For me, designing is really about creating conversation, creating emotion.

With the zine, the design was really important. In addition to allowing for me to have fun putting all of these really cool photos and colors and textures together, I knew who I was designing it for: kids, other Autistic kids.

Other moms are trying to navigate their way through [finding spaces for their Autistic kids]. Some moms feel they have to isolate their kids or that they have to isolate themselves. They don't always understand their kids, so that's a big struggle in itself.

Really, for me, it's about putting [Knox] in spaces to see him just be himself. That's it. That's all I have to do. I don't have to try to regulate his behavior, I don't have to try to make him adapt to certain surroundings. No, it's the exact opposite. It's really just about watching him live his life.

All that I need to do as a parent is just enjoy him, because in the blink of an eye, he's going to be 30 years old. And I'm going to be wishing that I can go back to these moments.

When sharing and discussing this story, please note that Autistic people (like anyone!) prefer the use of inclusive language. White-Johnson recommends using Identity First Language over Person First Language.

Here’s a quick breakdown:

Identity First Language (IFL): “I'm Autistic, and that takes nothing away from the fact that I'm a person (not a person with Autism) first and foremost.” [preferred]

Person First Language (PFL): “I am a person. Not a person with Autism or anything else.”

We hope that these resources will help you share the story of Knox Roxs!

Autistic Artists and Creators

Btrcp (Stephen McDowell): DMV-based Autistic artist and author of #umcomic. They/them.

Beth Wilson: UK-based rainbow cat artist. EDS, CFS/ME. She/They.

Mariah Person: Autistic dancer at the union for contemporary art in Omaha, Neb. Express Unbound is a multimedia environment and participatory performance that explores Autistic experiences through art and movement. Become part of a sensory experience and explore expression through emotional regulating movements called stimming.

Autistic Advocacy

Networks and Activists

Lydia X. Z. Brown, Esq: Writer, advocate, organizer, strategist, educator, speaker, attorney. Founder and co-director of the Autistic PoC Fund.

The Aspergian: A neurodivergent collective.

Art With a Heart: An organization that partners with Autism Society of Baltimore to hold workshops for neurodiverse kids and families.

BodyWise Dance: Director Margot Greenlee leads therapy-informed performing arts training for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the DMV area.