Dollar Bills and Sideshow Thrills

Reclaiming weirdness in DC’s underground sideshow culture.

Words and Photographs by Toby Cox

A single flame flickers, dancing on invisible air currents.

It appears almost tame, but Dr. Michelle Carnes is not fooled—they see its appetite for destruction, how it tirelessly stretches upward, reaching for something, anything, to extinguish its hunger. The cousin of wildfire, it’s this small flame’s nature to burn with an unmatched fury.

But Michelle has other plans.

They quiet the instincts screaming at them to not do what they are about to do. Looking beyond the flame, they see nothing but the darkness. They and their flame are all that exist. They bring the torch to their face, allowing themself to feel its heat. They open their mouth and place the torch on their tongue. Later, it will feel as though they swallowed jalapeño oil, but for now, their saliva protects them. They devour the flame, and it surrenders, its last words a soft “wha-cha” sound that is audible to no one else.

In that moment, Michelle became a fire eater, adopting the stage name Dr. Torcher.

“It was dark, and I couldn’t see the audience, just fire, fire, fire,” Dr. Torcher said. “I could hear the audience, though. Everyone was screaming. People love fire.”

Dr. Torcher made their debut as a fire eater in 2015 on the stage of the DC Weirdo Show, a local underground variety and sideshow. Little did they know, they and their partner, Mark Anduss, would produce the show themselves later that year.

With the help of the local community, they transformed the DC Weirdo Show into one that entertains with “freaks, geeks and exposed buttcheeks” — and informs on social justice issues related to race, gender, and sexuality, both on the sideshow stage and within society as a whole.

“It was dark, and I couldn’t see the audience, just fire, fire, fire.”

The history and culture of sideshow are tied to the history of the circus, which arrived in the U.S. in 1793. The circus reached its peak in the 1880s, when P.T. Barnum and James Bailey decided to put aside their rivalry and join forces. The result was Barnum & Bailey’s “The Greatest Show on Earth,” which outperformed competitors and became the pinnacle of circus entertainment. It boasted a lineup that valued spectacle, exotic animals, and a living “museum” that displayed human “oddities,” laying the foundation of the American sideshow.

Human “oddities” referred to those who could do weird, amazing things: contortionists, fire eaters, glass walkers, sword swallowers, and burlesque performers. The term also referred to people who appeared outside the “norm” in 1880s America — the differently abled, people of color, and those from the LGBTQ community. Circus productions were meant to reinforce this divide, with the audience being “normal” and the performers being “weird” or the “other.”

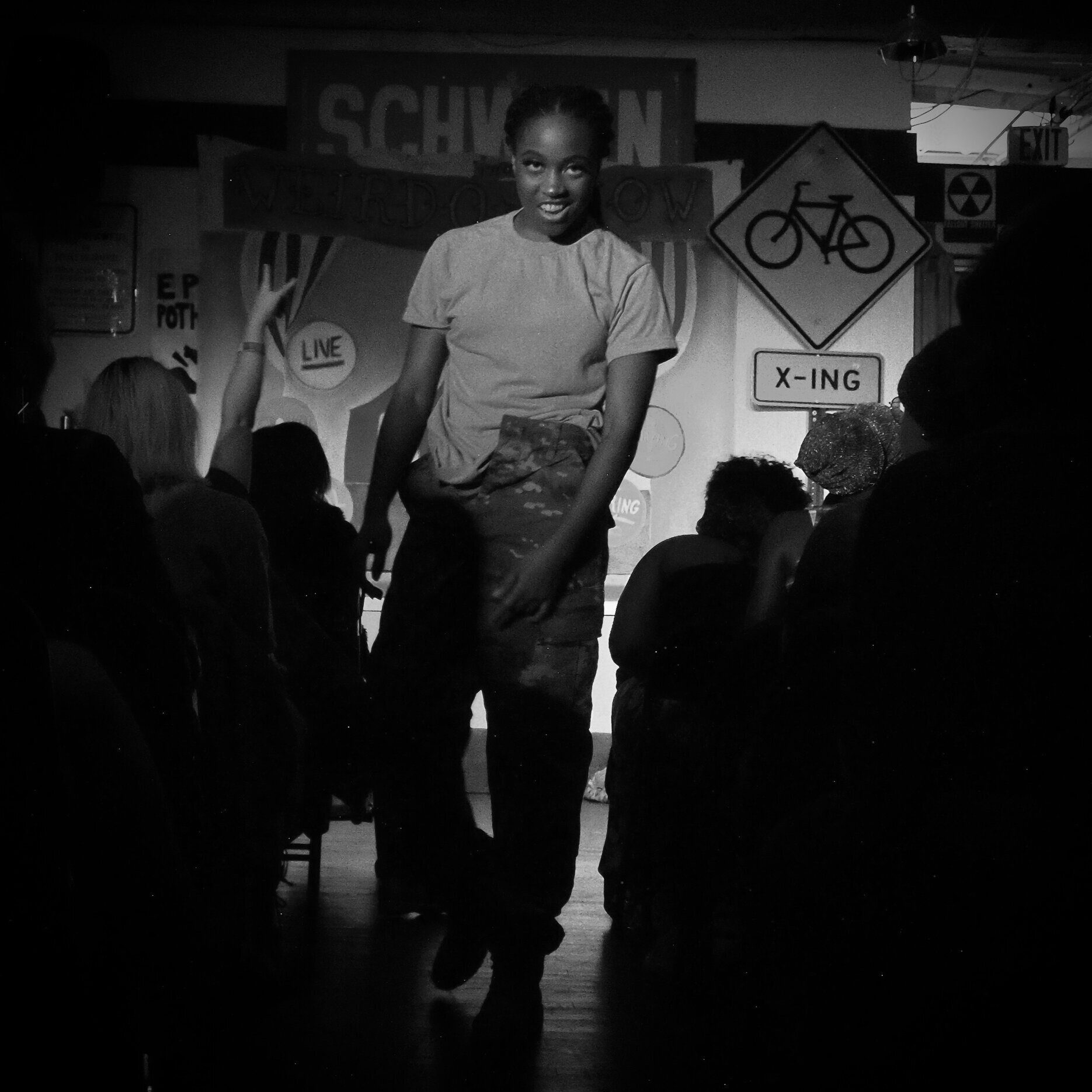

L-R: An audience member listening for their raffle number to be called. | KaaMani Sutra (they/them) is a sideshow performer who specializes in drag art. Sutra wishes people knew that sideshow is a “space for a different form of art, not just one particular art.” | Esther Gin’s (she/her) performance was entitled “Invisible Woman” and is an act about self-discovery. “I'm a trans woman who wrestled with self-doubt and self-hatred for a long time on the road to my own end. ‘Invisible Woman’ is not, however, only my story, or only the story of a trans person. It's for anyone who has ever hidden in plain sight. It's for anyone who has ever wished they could just disappear. It's for anyone who has ever felt observed, but not seen. For anyone who has scars which they hated earning but are proud of all the same.”

The DC Weirdo Show rejects this narrative and the culture that sustains it today. Dr. Torcher and the show’s community hold the DC Weirdo Show accountable for sideshow’s history, choosing to embrace “weird” as a modifier that unites rather than divides.

When Dr. Torcher was first exposed to sideshow culture, they didn’t like how sideshow adopted a “look-what-I-can-do-and-you-can’t” attitude that created distance between the performers and audience members. Instead of emphasizing the differences between the performers and the audience, Dr. Torcher prefers an atmosphere that brings everyone together and highlights their shared humanity.

“I thought it was more important to make it clear that when I stick a sword down my throat, you have an esophagus just like I do,” Dr. Torcher said. “It would take work and practice, but hypothetically, you could learn to do it, too.”

For Dr. Torcher, sideshow is more than the weird, amazing things people can do. It’s about exploring the deepest dimensions of the human psyche and celebrating the spectrum of human identity.

“We’re all weird in some way, whether we are born weird or make ourselves weird,” Dr. Torcher said. “We’re all together in this, which is what I think sideshow is really about.”

Sage (they/them) specializes in pole dance, burlesque, and drag and has performed at the DC Weirdo Show multiple times. “My time there [with the DC Weirdo Show] was one of the first places where I was celebrated for being more than 50% of myself. I'm grateful for that.”

However, people within sideshow culture do not always see it this way.

Historically, performers of color had little opportunity to fully control their narrative on stage: They were often not allowed on stage at all, or advertised as exotic spectacles. Today, dance is still often seen as a feminine art, while acts such as fire eating, sword swallowing, and angle grinding are associated with masculinity — especially white masculinity.

Although a lot has changed in sideshow since its beginnings, mainstream sideshow culture remains protective of its roots. Many sideshow productions in D.C. still feature casts that are mostly white and performances that perpetuate the idea that certain acts are reserved for certain people, whether that’s based on gender, race, sexuality, or body type.

“With a lot of other companies and troupes in the area, you see the same body type, the same races, and the same kinds of acts over and over and over again,” said Max Snax, a regular DC Weirdo Show supporter. “In the DC Weirdo Show, I see thin people, fat people, white, brown, and Black people — people from clearly very different backgrounds and experiences. It was really clear that people were invested in telling stories through their acts and that they were trying to do something different.”

That isn’t an accident. One of the first things Dr. Torcher did when they took over the show was make it more representative of the D.C. community.

“The majority of our performers on stage are Black and/or queer, and our show is also ASL interpreted,” Dr. Torcher said, “because when you think about who lives in D.C., you find a huge Black population, a huge queer population, and a huge deaf population.”

In April 2019, the DC Weirdo Show’s theme was “Queer Sideshow.” The show featured performers from the LGBTQ community, including Dr. Torcher, who appeared as their drag king persona, Sideshow Bro. The show also featured belly dance, drag, fire stunts, a mermaid, a bed-of-nails stunt, and sword swallowing — all by local performers from the queer community.

“An entirely queer-performer, sideshow-focused show has been a dream of mine since the show was given to us,” Dr. Torcher said. “Queer people have always been a part of the circus and sideshow, and it feels great to use our platform to tell our stories, in our voices, on our terms.”

When the stage is more accessible, audience members can end up feeling more included, too. At the DC Weird Show, it’s easy to measure the audience’s enthusiasm, in the form of the wadded up $1 bills showered upon performers during their acts.

“It’s not that I want to go to the show because I know I’ll be represented — it’s that I didn’t even know I wasn’t being represented until I felt that validation from performers I could relate to,” Snax said.

To empower performers from different backgrounds to share their stories, Dr. Torcher began collaborating with local performers to put on entire productions, lending the DC Weirdo Show stage to those unable to produce shows on their own, financially or otherwise.

Leigh Crenshaw-Player, a D.C.-based comedian, life coach, and content creator, collaborated with the DC Weirdo Show two years in a row to produce a show called “Unforgiveable Blackness.”

“For local Black and queer performers, there’s been sort of a wear and tear happening from being part of a scene that’s not necessarily the most trans-friendly, queer-friendly, or Black-friendly,” Crenshaw-Player said. “I wanted to pull together an all-Black show that celebrated our resilience, beauty, and excellence.”

—

From the moment they took over the DC Weirdo Show in 2015, Dr. Torcher knew they would eventually give it up, and the November 2019 production signaled a significant shift from its previous monthly format. From that point forward, Dr. Torcher and the DC Weirdo Show have stepped out of the spotlight to support performers of color as they create their own shows (which will resume once it’s safe for audiences to gather in confined spaces).

“The future of DC Weirdo Show is exactly that–behind the scenes, to elevate and strengthen especially Black and Brown leadership in show production,” Dr. Torcher said.

Because the show has fostered a reputation based on supporting local performers and holding sideshow accountable, it’s easy to envision the DC Weirdo Show’s future. The local community will continue to show up and file into the room until it reaches capacity. They’ll wonder what’s in store for them, and they’ll get their $1 bills ready. Regardless of the evening’s theme, however, the audience can count on a production that introduces them to talented performers and poses essential questions about race, gender and acceptance.

And, of course, don’t forget the abundance of exposed buttcheeks.